Recent dialogues among scientists and the public indicate a growing consideration that consciousness is not solely a human trait but one potentially shared across a much broader range of species. Throughout human history, we have deemed ourselves distinct in our ability to think and feel, placing humans at a hierarchical peak. Traditionally, the concept of consciousness is often equated with self-awareness and high cognitive functions which are believed to be absent in most other animals. This anthropocentric viewpoint has been challenged, especially with recent studies suggesting that animals, even insects, might possess forms of consciousness. The implications of these discussions are profound, not only affecting scientific paradigms but also altering ethical standards and behaviors towards other life forms.

The notion posited by some scientists that even insects like bees might have a form of consciousness called ‘phenomenal consciousness’ suggests a basic level of sentience capable of experiencing sensations like pleasure or pain. If a bee derives joy from playing with a ball, as some behaviors observed in controlled environments suggest, it leads to intriguing biologically sensitive queries. Can these activities be dismissed as insignificant mechanical responses, or do they hint at something deeper, analogous to what humans might describe as ‘fun’?

This introduces a complex web of philosophical debate. It is one thing to determine through scientific inquiry whether an animal exhibits behaviors indicating potential consciousness; it is another to ascribe a qualitative experience to these behaviors. Ascribing human-like reasons to animal actions—anthropomorphism—can skew our interpretations. When bees play with balls or birds participate in seemingly joyous activities, are we observing genuine pleasure, or are these merely evolutionary adaptations to enhance survival skills, such as better coordination or social bonding?

Furthermore, the ethical ramifications are immense. If we accept that various animal species have forms of consciousness, this realization pressures us to reconsider how we treat them. From industrial farming practices to laboratory experiments, the moral grounds of our interactions with animals are called into question. If a bee feels pleasure, does it not also feel distress? The push for recognizing animal consciousness invites a broader discussion about animal rights and the humane treatment of all sentient beings.

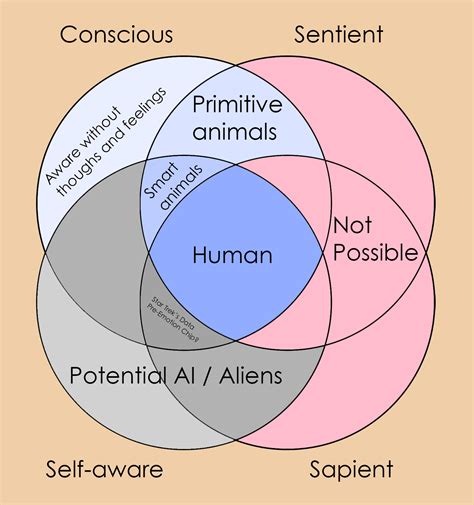

The scientific pursuit to understand consciousness in animals also stumbles upon technological and methodological limitations. Terms like ‘consciousness’ and ‘sentience’ are often used interchangeably, yet their definitions vary and are subjected to individual or cultural interpretations. The challenge lies not only in defining what consciousness is but also in developing methods to objectively measure and understand it across species. This challenge is reminiscent of the ‘streetlight effect’, where researchers may only be looking where it is easiest to find data, thereby potentially overlooking crucial aspects of animal cognition and experience.

In conclusion, the discourse around animal and insect consciousness is not merely an academic one; it pivots on deeply ingrained notions of life, existence, and ethics. As we deepen our understanding of the animal kingdom, we must tread cautiously, recognizing our biases and the limitations of our tools. By bridging the gap between scientific inquiry and ethical consideration, we might not only expand our knowledge but also cultivate a more compassionate and respectful coexistence with all forms of life.

Leave a Reply