In a stark and unsettling revelation, the United States has found itself at the top of an undesirable list: it has the highest rate of maternal deaths among high-income nations. This is in sharp contrast to countries like Norway, which boasts a maternal mortality rate that has reached an impressive—and in some ways, unbelievable—zero. The question that looms large is why are these countries performing so differently in such a critical health metric, and what lessons can the U.S. learn to make significant improvements?

One critical factor to consider is the nature of the healthcare systems in play. The United States operates a predominantly privatized healthcare model, where access and quality of care are often contingent upon one’s financial status. This model stands in stark contrast to the Nordic model observed in countries like Norway, where government-funded, single-payer healthcare systems ensure that all mothers-to-be receive consistent, high-quality care irrespective of their financial situation. Programs like Medicaid do exist, but they often serve as a fragmented patchwork rather than a comprehensive safety net. Critics argue that a move towards a single-payer system could significantly alleviate issues related to access and quality of care.

The concept of baby boxes, common in some Nordic countries, particularly Finland, and frequently misconstrued in the U.S., also merits attention. In Finland, these boxes are filled with essential baby supplies, ensuring that every new mother has access to the basics she needs to care for her newborn. It’s not just about the physical items; it’s a symbolic gesture that underscores the state’s commitment to the health and well-being of its youngest citizens and their parents. The U.S., while having baby hatches at many fire stations, has not universally adopted the practice of providing comprehensive supply kits, which could be a low-cost yet impactful public health intervention.

Another cornerstone of Norway’s success is its robust maternity leave policy and supportive social framework. Norwegian mothers receive a generous amount of maternity leave, along with access to prenatal and postnatal care that is deeply integrated into the healthcare system. This means regular check-ups, educational programs, and a predefined care path for pregnancies that are adhered to religiously by healthcare providers. By contrast, in the U.S., maternity leave policies vary widely, dependent on the employer, and often do not meet the needs of working mothers. Ensuring that women have adequate time to care for themselves and their newborns without the stress of potential job loss is crucial for reducing maternal mortality rates.

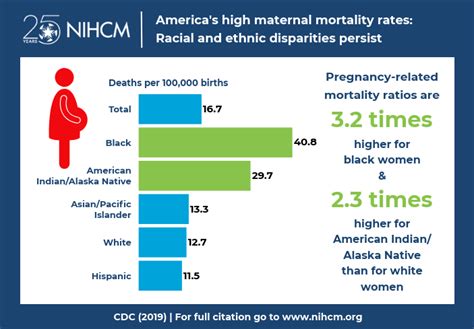

Another vital aspect is the endemic issue of healthcare provider bias in the U.S. Towards patients on Medicaid or uninsured patients. Discrimination and stigma can significantly affect the quality of care these patients receive, leading to poor health outcomes. This bias is compounded for women of color, who statistically face even higher risks during childbirth. Addressing this bias begins with comprehensive training for healthcare providers about implicit bias and making sure that policies in place prevent such disparities. Improving the healthcare system is not just about structural changes but also about addressing the nuances of everyday medical practice.

The emphasis on profit within the U.S. healthcare system cannot be overlooked. The incentive structures are geared more towards generating revenue for hospitals and healthcare providers rather than ensuring optimal health outcomes. This profit-driven model leads to a higher focus on expensive, often unnecessary procedures, and less on essential, preventive care that could drive down maternal death rates significantly. For instance, emergency care is often prioritized for its profitability, whereas consistent prenatal care, which might seem less profitable in the short term, has been proven to significantly lower complications leading to childbirth fatalities.

Lastly, the overarching cultural attitude towards maternal health in the U.S. often pits individual responsibility against systemic responsibility. The narrative that health is an individual responsibility overlooks the systemic barriers that numerous Americans face. While there is significant merit in promoting healthy lifestyles, an overemphasis on personal responsibility neglects the fact that not everyone has equal access to the means to make those choices. Public health interventions should address such disparity by ensuring that basic prenatal and postnatal care is accessible and affordable to every mother, thereby enhancing the overall health standard for maternal care.

The discrepancy in maternal mortality rates between the U.S. and countries like Norway should serve as a catalyst for a transformative re-evaluation of maternal healthcare in America. From systemic healthcare reforms to education and policy changes, there are multiple strategies that, if implemented, could make a substantial difference. It is high time for the U.S. to look outward, adopt best practices from other nations, and tailor them to improve the dire maternal health statistics at home.

Leave a Reply