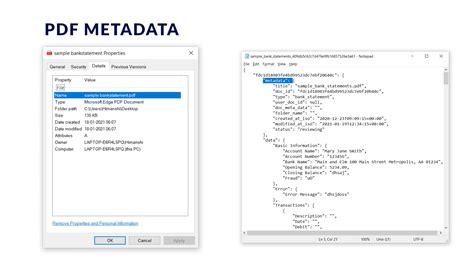

In the ever-evolving landscape of digital content management, a recent spotlight has been cast on Elsevier’s practice of embedding unique hashes in the PDF metadata of each downloaded document. This revelation has sparked a fervent debate about the balance between protecting intellectual property and respecting user privacy. For those unfamiliar, a hash in this context serves as a digital fingerprint, uniquely identifying each downloaded PDF document. While this may seem like a sophisticated strategy to combat piracy, it raises critical questions about user rights and the transparency of such practices.

The practice of embedding unique identifiers in downloaded files is not new, but Elsevier’s approach has brought this to mainstream attention. As pointed out by commenters like vsuperpower2020, obtaining documents from multiple sources and comparing their hashes could be a prudent strategy to verify authenticity before publication. This is particularly relevant in an age where digital content spans not just PDFs but also images, audio files, and programs. The core of the issue lies in the transparency—or lack thereof—regarding how these unique hashes are utilized and monitored.

A sentiment echoed across various discussions is the apparent lack of a ‘cookie nagger’ on Elsevier’s PDFs, which might suggest leniency in other areas of compliance. Commenter Y_Y notes the absence of such nags, hinting that there might be other regulations or practices Elsevier could leverage more effectively. Meanwhile, ndr highlights the potential complexities of dismantling such a practice under the guise of ‘legitimate interest,’ a legal term often used to justify data processing without explicit consent.

Strategies to circumvent these embedded hashes are plentiful and varied, suggesting a level of distrust or dissatisfaction among users. For instance, hristov offers a simple procedure: download the PDF, open it in a viewer, and print it to a new PDF file. This supposedly removes the unique hash, though the effectiveness of such methods can vary. Other users propose more elaborate methods, such as converting files to images or plain text to entirely eliminate any hidden identifiers, as described by commenters like antegamisou and bArray.

Despite these potential workarounds, the core concern remains—whether such practices violate user privacy. In academic circles, especially, this has broader implications. Imagine working tirelessly on a research paper only to find it trackable through various subtle watermarking techniques. As pointed out by nonrandomstring, the use of metadata for document watermarking might extend beyond what is visible, incorporating spacing, kerning, and even invisible characters to create unique digital fingerprints. These practices might seem invasive to many, drawing sharp criticism and calls for more open, transparent practices.

The implications of these practices extend beyond mere privacy concerns. The strong reactions from users and academics alike indicate a deeper dissatisfaction with the current state of academic publishing. Comments from the likes of bayindirh and epolanski reflect a broader frustration with costly publishing models and the power dynamics within academic publishing. The sentiment that Elsevier and similar entities act as ‘social parasites’ is strong, with calls for more open, FAIR (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable) science and better access to public knowledge.

Interestingly, the conversation often pivots toward potential disruptors in the academic publishing world. Platforms like arXiv have revolutionized how preprints are shared within the scientific community, demonstrating a viable alternative to traditional, for-profit publishing houses. As noted by commentors such as __rito__, these platforms have gained significant traction, especially in fields like AI research. The momentum towards open access is undeniable, but the path is fraught with challenges, particularly those related to maintaining quality and peer-review standards.

In conclusion, Elsevier’s practice of embedding unique hashes in PDF metadata raises significant privacy concerns and questions about the future of academic publishing. While there are clear motivations for such practices, rooted in the protection of intellectual property, the backlash suggests a need for more balanced, transparent approaches. As the open access movement continues to gain steam, it will be crucial to find innovative solutions that protect both the rights of content creators and the privacy of users. Ultimately, the goal should be to foster a more inclusive, accessible, and fair academic publishing ecosystem, free from the constraints of outdated, exploitative models.

Leave a Reply